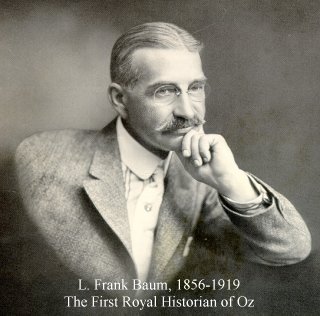

L. Frank Baum, the Royal Historian of Oz

Who was L. Frank Baum?

Born in Chittenango in upstate New York on May 15, 1856, Lyman Frank Baum was the son of wealthy parents. He had a happy childhood, but Frank was a dreamer, and for a long time after leaving home he was not much of a success at anything. He tried acting, selling machine oil and crockery, managing a department store, and newspaper editing and reporting, but nothing seemed to work well for him or hold his interest for long. He finally started writing when his mother-in-law encouraged him to write down the fanciful tales he'd been telling his four sons and their friends for years. Although he initially had trouble finding a publisher, his works eventually caught the attention of the public, and he was able to finally make a decent living. Although he also dabbled in theater production and the fledgling motion picture industry, he kept on writing books for the young at heart until his death at Ozcot, his Hollywood home, on May 6, 1919.

What did the L. stand for?

Lyman. It was a name he hated, and he went by Frank all of his life. As an actor, he sometimes used the name Louis F. Baum, and as a newspaper editor he usually signed his editorials L. F. Baum. He used L. Frank Baum on all of his published works (except for those published under a pen name, of course.)

How did he come to write The Wonderful Wizard of Oz?

Like most of his early writings, it started off as a story he was telling his sons and their friends in 1898. At that time in Frank's Chicago neighborhood, a number of children would come to the Baum's house to listen to his stories in the evening. He came to Dorothy meeting the Scarecrow when one of his listeners asked, "Mr. Baum, where did they live?" He thought about it for a moment, and replied, "The Land of Oz," and continued the story. (For details on how he may have come up with the name so quickly, see Where did the name Oz come from?.) Later that night, his wife, who had also been listening as she worked on her sewing, urged Frank to write the story down, and he quickly produced a manuscript. His friend W. W. Denslow agreed to illustrate it, and they tried to find a publisher. But at that time American publishing firms were only interested in children's stories from European, and especially British, writers. Nobody was interested in publishing an American fairy tale, because it had never been done before. Finally, Baum and Denslow struck a deal with the publisher of their previous book. The Wonderful Wizard of Oz was published May 15, 1900, and became the biggest selling children's book of the year. (There is a story that late in 1900, Baum, needing money for Christmas, asked the publishers for his royalties to date in December, and took the check from them without looking at the amount. When he got home and gave it to his wife, she nearly collapsed, because it was over $3000, a small fortune in those days.)

What authors influenced Baum?

This is a hard question to answer, primarily because nobody can say for sure. Baum was a fan of Charles Dickens, however, and so was probably influenced by him. Lewis Carroll, of course, was a major influence, as his Alice books were so new and popular, and have many similarities to the Oz books, as well as Phunnyland/Mo in A New Wonderland/The Magical Monarch of Mo. Nathaniel Hawthorne also seems to have influenced Baum, as his story "Feathertop," popular in the 19th century, seems to be the inspiration for the Scarecrow, Jack Pumpkinhead, or both characters. (Several websites now carry "Feathertop," so you can read it for yourself at http://www.online-literature.com/hawthorne/135/ or http://www.classicreader.com/read.php/sid.6/bookid.284/, among other sites.) Baum spoke highly of other writers in newspaper interviews, but in many cases, the editions of their works in his library had never been read.

What were Baum's political beliefs?

I think I see where you're headed here; you want to know what political agenda Baum was trying to write into his book. For more information, including Baum's political background, see the question Is it true that The Wizard of Oz was written as a political tract?

Was Baum a racist?

There's no simple answer to this question. Baum's writings contain ethnic caricatures and opinions that would be shocking and unacceptable if first written and published today. But to understand his values we need to compare his words to those of other Americans at the time.

In Baum's fiction, some passages clearly reproduce racial stereotypes of his day. His "official" Oz books are fortunately free of these, with the notable exceptions of short passages in The Patchwork Girl of Oz and Rinkitink in Oz (see the second paragraph of the question Have the Oz books ever been banned, edited, or censored? for details). But some of the adventure stories Baum wrote for teens contain now-unacceptable words and sentiments. Set in an American city, The Woggle-Bug Book is a veritable parade of ethnic stereotypes, complete with speeches written in dialect. There's a disparaging remark about servants made of chocolate in Dot and Tot of Merryland, and ethnic caricatures in some poems in Father Goose: His Book. The original illustrations in these books also include racial caricatures; though Baum wasn't responsible for that art, he seems to have raised no objections.

We can see Baum's writings reflect the racism of his society in another way by looking at what they leave out. All the heroes and heroines of his books appear white — indeed, judging by their last names, nearly all the Americans are of British ancestry. All the ordinary humans we meet in Oz (except the Tottenhots) appear white. This pattern is less obvious than broad racial caricatures, but still exclusionary. Like most Americans of his time, it seems, Baum considered white skin to define the norm. But as illustrations of her in other countries and the success of The Wiz stage musical (see the question Was The Wizard of Oz or any other Oz story ever performed as a play?), and Ashanti's portrayal of Dorothy in The Muppets' Wizard of Oz show, Dorothy Gale can be depicted successfully as being of any ethnic background.

At the same time we acknowledge those patterns, we should note that Baum's Oz books generally champion the value of folks learning to live together. Sometimes this message comes in the same passages that contain offensive stereotypes. The Tottenhots episode in The Patchwork Girl of Oz ends with them and Dorothy agreeing, "you let us alone and we'll let you alone." When Baum's movie studio filmed that book (see the question Have there been any Oz movies?), the Tottenhots were played by white men made up to reflect stereotypes of "African savages"; yet one Tottenhot sits on an Emerald City jury alongside the Scarecrow and Tin Woodman, at a time when many parts of the U.S. excluded African-Americans from jury pools.

Baum's attitude stands out when we look at how the American culture around him depicted blacks. Racial stereotypes far nastier than the Tottenhots pervaded popular literature, theater, and early film. Few white authors wrote about African-American children, and those who did usually rendered them as clowns. Compared with many contemporaries, Baum's use of racist stereotypes appears mild and infrequent.

Much more disturbing, however, are two short newspaper essays on Native Americans that Baum published years before he started writing for children. In January 1890 Baum bought the weekly Aberdeen Saturday Pioneer in Aberdeen, South Dakota. That new state contained several shrinking federal reservations for the Lakota, Dakota, and Nakota peoples, also collectively called the Sioux. Later that year, many Native Americans joined the "Ghost Dance" religious movement, which prophesied the return of Jesus as a Native American. Alarmed by this cult and the independence it inspired, federal police officers went to arrest the retired general Sitting Bull and ended up killing him on December 15. Two weeks later, the U.S. Army massacred hundreds of Sioux camped at Wounded Knee. On December 20, 1890, and January 3, 1891, Baum wrote short editorials about these events. He lamented Sitting Bull's death but declared all remaining Indians to be "a pack of whining curs" and called for their "extirmination" [sic].

For these writings, some have compared Baum to Adolf Hitler. His defenders, on the other hand, have argued that Baum wrote satirically, as Jonathan Swift did in "A Modest Proposal" (which you can read at http://art-bin.com/art/omodest.html), for example. Baum usually did write with a great deal of irony, especially in his "Our Landlady" columns (see What other books did Baum write?). When a group of Dakota had visited Aberdeen for Independence Day, he'd poked fun at both them and the locals, including himself. As late as December 6, he'd supported the Indians' freedom to worship how they pleased. But if Baum meant his December 20 editorial to be ironic, it's hard to explain why he repeated and amplified the same message after learning that the U.S. army had actually killed men, women, and children at Wounded Knee.

Let's be honest here: What Baum wrote about Native Americans in late 1890 and early 1891 is short-sighted, bigoted, and repugnant. This was also the only time he ever advocated genocide. As described above, his earlier newspaper writings and later children's books promoted tolerance. So the real mystery is why Baum suddenly expressed so much hostility toward Native Americans. To understand that, we have to examine the context in which Baum wrote. Our best sources are Baum's Road to Oz: The Dakota Years and Our Landlady, both books edited by Nancy Tystad Koupal.

To begin with, Baum was far from the only South Dakotan expressing animosity towards Native Americans at that time. The sentiment that all noble Indians had died, leaving a degraded race, was unfortunately deep-rooted in American culture. It appears in writings by Thomas Jefferson, James Fenimore Cooper, H. Rider Haggard, and many others. Friction between the Sioux, forced to live on a small portion of the land they'd once roamed freely, and white settlers was inevitable. The "Ghost Dance" movement promised that all whites on the continent would soon be buried under a thick layer of new topsoil. In late 1890 Aberdeen was filled with rumors of Sioux groups on the move and farmers feeling besieged. The dominant Aberdeen Daily News argued for arming white settlers and said, "Put it in the hands of practical men and the Indians who were not 'good' would be few and far between without much ado, or waste of time." Baum's essays thus went farther than anything his neighbors said in print, but they came at a time when hostility and fear were widespread. So far as we know, no one in Aberdeen condemned his remarks.

The second important factor is what was going on in Baum's own life. South Dakota's crop failures and the state Republicans' loss in the November elections meant that the Saturday Pioneer was losing subscription and ad revenue (the Pioneer had always been a Republican-leaning paper). Maud Baum was pregnant with the couple's fourth child. Baum also seems to have become seriously ill around that time. Those pressures must have affected Baum's outlook when he wrote. And his columns weren't like newspaper editorials today, debated and reviewed by boards. Baum wrote his comments quickly to fill empty space left by the news, perhaps even composing remarks off the top of his head.

Baum had long been "noted for being contrary," according to the Daily News, but at the end of 1890 he seemed to lose much of the optimism and humor that had lightened his essays. In February he stopped writing "Our Landlady." His 1891 editorials picked fights with the town's ministers, fire department, school administrators, and eventually high school students. By April, Baum sold the newspaper and moved to Chicago. He never again wrote about Native American policy. Taken in that context, Baum's editorials on Sitting Bull and Wounded Knee seem less like deep-seated convictions and more like the remarks of a man under stress expressing anger and fear in a way that his society allowed.

Baum was a product of the nineteenth century, born five years before the Civil War began. During his life, and long after, the United States was a segregated society in which European-Americans held power and set policy. People of all other ethnic backgrounds were denied equal services, opportunities, and respect. Even other European groups, such as Irish, and Italians, suffered from prejudice and discrimination. Within that society, many of Baum's beliefs were progressive, but since then our values have become much more inclusive. For example, Baum and his relatives spent decades advocating women's suffrage, and today no politician would conceive of saying that only one sex should be allowed to vote. We therefore can't judge Baum solely by twenty-first century standards.

When we understand the intellectual environment of Baum's time, it's no surprise that his stories occasionally portray non-white people as inferior. His newspaper remarks on Native Americans may come as a shock, but they also appear to be an aberration within his writings. Baum expressed racism, but simply labeling him as racist neglects how he differed from his contemporaries. It also overlooks how his best-loved books show young readers a society of many peoples, differing greatly in culture and tastes and even physical makeup yet living together with happiness and mutual respect.

(Many thanks to J. L. Bell for his assistance and comments in writing the answer to this question.)

Why did Baum write a whole series of Oz books?

Frank had many, many ideas for stories, and he tried to tell as many as he could. But none of his books sold as well or generated as much interest as The Wonderful Wizard of Oz. The success of the 1902 stage show also made Oz a recognized name. So when he went to new publishers in 1904, the first book they wanted from him was a new story about Oz. Originally entitled The Further Adventures of the Scarecrow and Tin Woodman, the publishers wanted Oz in the title, so it became The Marvelous Land of Oz (later shortened to The Land of Oz, now available under both titles — see the question What's the difference between The Marvelous Land of Oz and The Land of Oz?). While this kept readers happy for a while, they wanted to know more about Dorothy and the Cowardly Lion, neither of whom had appeared in the new book, so Frank wrote a third Oz book, Ozma of Oz, and then some more ideas for other Oz books came to him, some from his fans' letters. He tried to end the series with The Emerald City of Oz in 1910, but bankruptcy and the disappointing sales of his other new books prompted him to return to Oz in 1913, and from then on he wrote an Oz book every year for his demanding readers for the rest of his life. The Magic of Oz was in production when he died in 1919, and Glinda of Oz was published posthumously a year later.

What other Oz stories did Baum write?

In addition to his fourteen Oz novels, Baum wrote a number of short stories and one related book, all dealing with the Oz characters. First came "Queer Visitors from the Marvelous Land of Oz," a series of Sunday comic pages, illustrated by Walt McDougall and published in a number of newspapers from late 1904 to mid-1905. These were not comic strips as we know them today, but a full page, containing an illustrated short story. Some of McDougall's illustrations show elements of the modern comic strip, however, most noticeably word balloons for dialogue. There were twenty-six installments. In the comic the Scarecrow, the Tin Woodman, Jack Pumpkinhead, the Sawhorse, the Wogglebug, and the Gump, all from the book The Marvelous Land of Oz, have a number of strange experiences and exciting adventures in a far-off land called America. They even met Dorothy in Kansas. A book that was spun off from this series, The Woggle Bug Book, illustrated by Ike Morgan, tells of the Wogglebug's adventures on his own, after being separated from his companions (this was at the time of a short-lived Wogglebug craze). It is much poorer than the Oz books, has not dated well at all, and did not remain in print very long. And the only character from the Oz books is the title insect. It was available in a reprint edition from Scholars' Facsimiles and Reprints, and as part of the anthology Oz-Story 5 from Hungry Tiger Press. The Woggle-Bug Book is also available now from the print-on-demand publishers Lulu.com.

Nobody knew of the "Queer Visitors" comic for a long time, until Oz historian, collector, and artist Dick Martin rediscovered it in some newspaper archives in the late 1950s. He immediately saw the potential for a book, and convinced Reilly and Lee to publish it. Some of the stories were adapted by editor Jean Kellogg, and The Visitors from Oz, illustrated by Martin, came out in 1961 under Baum's name. It is no longer in print. (Another book called Visitors from Oz, written by Martin Gardner, was published in 1999. Other than the title and the basic premise of Oz characters visiting America, there is no relation between the two books. Gardner's book is entirely his own creation.)

More recently, all of the original "Queer Visitors" stories and a slightly edited version of the text of The Woggle Bug Book were collected into The Third Book of Oz, called that because it must logically take place after The Wizard of Oz and The Land of Oz in the series, but before Ozma of Oz. It was illustrated by Eric Shanower, with an introduction by Martin Williams. It is currently out of print. This has now been reprinted as the book The Visitors from Oz, the third book to bear that name, published by Hungry Tiger Press in 2005.

Finally, all of the original "Queer Visitors" pages were reprinted, in their original size, in the book Queer Visitors from the Marvelous Land of Oz: The Complete Comic Strip Saga 1904-1905. This came out from Sunday Press Books in 2009.

In 1913, to publicize the relaunching of the Oz series after a three year hiatus, Baum wrote a series of six short stories, intended for somewhat younger children, which were each published as separate books, similar in style to today's Little Golden Books, and they came out under the series title "The Little Wizard Stories." They were titled The Cowardly Lion and the Hungry Tiger, Little Dorothy and Toto, Tiktok and the Nome King, Ozma and the Little Wizard, Jack Pumpkinhead and the Sawhorse, and The Scarecrow and the Tin Woodman. A year later, Reilly and Britton collected them into one volume, The Little Wizard Stories of Oz. The stories remained in print for a number of years in various forms (four of them were given out as premiums during the 1933 radio show, for instance), but then went out of print for a very long time. In 1985 Schocken Books reissued The Little Wizard Stories of Oz (a paperback version of this book was issued by Bantam in 1988), and in 1994 Books of Wonder reprinted the book and Dover Publications released a trade paperback in 2011. Both these editions are still currently available.

One other Oz story by Baum that has been published was the inscription he wrote in the copy of The Road to Oz he gave to his first grandson, Joslyn Stanton Baum. Twenty numbered copies, under the title A Short, Short Oz Story, were printed in 1994 by Buckethead Enterprises of Oz. Baum also wrote a short story, "The Littlest Giant: An Oz Story," but other than its subtitle, there is no connection to Oz. It wasn't published until 1975, when it appeared in The Baum Bugle. It is available in the collection The Collected Short Stories of L. Frank Baum.

What other books did Baum write? Did he write under any pen names?

Baum was a prolific writer, and the Oz books were only part of his body of work. A number of his characters later show up in his Oz books, and in one case two Oz characters appear in one of his non-Oz fantasies after they first visit Oz. So, here is a list of Baum's books, divided into rough categories, with some annotations and explanations:

- I. Fantasies that are part of the world of Oz

- A New Wonderland (1900) — later edited, including changing the country's name from Phunnyland to Mo, with new material added, and reissued as The Magical Monarch of Mo (1903), currently available from Dover Publications. This was the first children's book Baum wrote. A New Wonderland is now also available from Lulu.com.

- Dot and Tot of Merryland (1901) — the last collaboration between Baum and Denslow. It is currently available, with new illustrations and some minor text alterations, from Books of Wonder.

- The Life and Adventures of Santa Claus (1902) — a fictitious biography of Santa Claus, and the only one of Baum's non-Oz books still generally available from a number of publishers. It was turned into a 1985 animated TV special by Rankin-Bass, a Japanese cartoon series, and a 2000 direct-to-video animated film from Sony. It was also adapted into a graphic novel by Michael Ploog. There may be a new film version coming out soon, too.

- Queen Zixi of Ix (1905) — considered by many to be Baum's best book. It is available from Dover Publications.

- John Dough and the Cherub (1906) — a new edition is available from Hungry Tiger Press. Dover also reprinted the book in 1974, and while it's out of print now, it may be easier to find or afford this than some others.

- The Sea Fairies (1911) — introduces Trot and Cap'n Bill, who later travel to Oz in The Scarecrow of Oz. It is available from Dover and Books of Wonder.

- Sky Island (1912) — another Trot and Cap'n Bill adventure, which also includes Button-Bright and Polychrome, both of whom first appeared in The Road to Oz. It is also available from Dover and Books of Wonder.

- A Kidnapped Santa Claus (1969) — a short story with many of the same characters and locations as The Life and Adventures of Santa Claus, published as a picture book in 1969. The story is also available in The Best of The Baum Bugle 1967-1969, available from IWOC, and with The Life and Adventures of Santa Claus in the book The Complete Life and Adventures of Santa Claus, published by Wildside Press.

- The Runaway Shadows and Other Stories (1980) — six Baum short stories, including "A Kidnapped Santa Claus," published by IWOC. Four of these stories take place in, or otherwise involve, the Forest of Burzee, which also appears in The Life and Adventures of Santa Claus, Queen Zixi of Ix, and other Baum stories, and Jack Snow's The Magical Mimics in Oz.

- II. Fantasies that appear to have little or no connection to Oz

- Mother Goose in Prose (1897) — short story collection of the tales behind some of the famous Mother Goose rhymes. Not only was this Baum's first published book for children, it was the first book illustrated by Maxfield Parrish. Some of these stories were adapted by Jim Henson, creator of the Muppets, for video and cable broadcast under the title Jim Henson's Mother Goose Tales, but not all of Henson's stories are based on Baum. This is currently available from Dover Publications.

- The Master Key (1901) — the closest Baum has come to science-fiction, although even then a magical demon influences events. It is available from Books of Wonder and Amereon.

- American Fairy Tales (1901) — short story anthology. Most of these stories take place in America, but a few take place in fairy countries. It is currently available from Dover Publications. Three additional stories were added to a later printing with a slightly altered title, Baum's American Fairy Tales (1908). The latter, with new illustrations, is available from Books of Wonder.

- The Enchanted Island of Yew (1903). This is currently available from Books of Wonder and other publishers. The title was also printed as The Enchanted Isle of Yew on some later editions.

- Jaglon and the Tiger Fairies (1953). This is an adaptation by Madeleine Kilpatrick, with input from Jack Snow, of one of Baum's Animal Fairy Tales (see below), published as a picture book.

- Animal Fairy Tales (1969) — anthology of fairy tales with animals in the lead roles. Originally printed serially in the magazine The Delineator in 1905, this was the first collection in book form, which is still available from IWOC. Another book edition came out from Books of Wonder in 1989, reprinting the original magazine layouts and illustrations, but it is not currently available.

- The Discontented Gopher (2006). This is the book edition of another of the Animal Fairy Tales, published by the South Dakota State Historical Society Press, with new illustrations by Cariolyn Digby Conahan.

- The Enchanted Buffalo (2010), another book version of one of the Animal Fairy Tales from the South Dakota State Historical Society Press, this one illustrated by Donald F. Montileaux.

- III. Non-fantasy works, including poetry collections and short story anthologies

- The Book of the Hamburgs (1886) — Baum's first book, about raising chickens, reprinted from some early periodical articles. It was reprinted by Books of Wonder in the 1990s, and is currently available.

- By the Candelabra's Glare (1898) — a privately published collection, Baum supplied the verse, friends donated the illustrations and materials, and Baum printed and bound the ninety-nine copies himself. It has been reprinted by Scholars' Facsimiles and Reprints and through Lulu.com.

- Father Goose: His Book (1899) — a collection of Baum's humorous verse and Denslow's drawings, and the biggest selling American children's book of 1899. It is currently available through Lulu.com.

- The Army Alphabet (1900).

- The Navy Alphabet (1900), now available from Applewood Books.

- The Art of Decorating Dry Goods Windows and Interiors (1900) — a technical book for window dressers, reprinting articles from Baum's magazine, The Show Window.

- The Songs of Father Goose (1900) — selected verses from Father Goose: His Book, set to music by Alberta N. Hall.

- Father Goose's Year Book (1907) — an illustrated desk calendar with new verses.

- L. Frank Baum's Juvenile Speaker (1910) — a collection of pieces from his previous works, designed for public speaking. It was later reissued as Baum's Own Book for Children.

- The Daring Twins (1911) and Phoebe Daring (1912) — these two books were adventure books aimed at older readers. The first book was reissued under the title The Secret of the Lost Fortune in 2006 by Hungry Tiger Press.

- The Snuggle Tales (1916 and 1917) — six small volumes reprinting some of his previous works, most from the Juvenile Speaker. They were Little Bun Rabbit, Once Upon a Time, The Yellow Hen, The Magic Cloak, The Ginger-Bread Man and Jack Pumpkinhead. They were reissued in 1920 as The Oz-Man Tales.

- Our Landlady (1941) — a collection of some of Baum's early newspaper columns.

- The Musical Fantasies of L. Frank Baum (1958) — a collection of Baum's scenarios for unproduced plays, and an essay by editors Alla T. Ford and Dick Martin on Baum's theatrical ventures.

- The Uplift of Lucifer (1963), the script of one of Baum's old Uplifters' shows. This was privately printed and given for free to Baum enthusiasts.

- The Purple Dragon and Other Fantasies (1976), a collection of fifteen Baum short stories.

- Our Landlady (1996) — a collection of all of Baum's "Our Landlady" columns from his newspaper days, edited and annotated by Nancy Tystad Koupal.

- The Collected Stories of L. Frank Baum (2006), collecting nearly all of Baum's short stories in one volume, published by and available from IWOC.

- Mention should also be made here of In Other Lands Than Ours, privately printed for the Baum family and their friends in 1907. It is Maud Baum's journal of the trip she and Frank made to Egypt and Europe in 1906. Frank wrote an introduction, edited, and took the photographs reproduced in the book. Scholars' Facsimiles and Reprints reprinted it in 1983. It is also available now from Lulu.com.

- IV. Baum's pseudonymous and anonymous works — these were mostly adventure stories for older children. The "author" name and date are given.

- The Last Egyptian (Anonymous, 1908), now available from Fredonia Books.

- Sam Steele's Adventures on Land and Sea (Capt. Hugh Fitzgerald, 1906), shortened on the cover of the first edition to Sam Steele's Adventures — reprinted in Oz-Story No. 1 in 1995 under Baum's name.

- Sam Steele's Adventures in Panama (Capt. Hugh Fitzgerald, 1907).

- The Boy Fortune Hunters in Alaska (Floyd Akers, 1908) — a reissue of Sam Steele's Adventures on Land and Sea.

- The Boy Fortune Hunters in the Panama (Floyd Akers, 1908) — a reissue of Sam Steele's Adventures in Panama. Reprinted by Hungry Tiger Press under the title The Amazing Bubble Car in 2008.

- The Boy Fortune Hunters in Egypt (Floyd Akers, 1908). Reprinted by Hungry Tiger Press under the title The Treasure of Karnak.

- The Boy Fortune Hunters in China (Floyd Akers, 1909). Reprinted by Hungry Tiger Press under the title The Scream of the Sacred Ape in 2006.

- The Boy Fortune Hunters in Yucatan (Floyd Akers, 1910). Reissued under Baum's name in 1998 by Hungry Tiger Press.

- The Boy Fortune Hunters in the South Seas (Floyd Akers, 1911). Reissued under Baum's name in 1998 by Hungry Tiger Press.

- Bandit Jim Crow, Mr. Woodchuck, Prairie-Dog Town, Prince Mud-Turtle, Sugar-Loaf Mountain, and Twinkle's Enchantment (Laura Bancroft, 1906) — a series of short books collectively called "The Twinkle Tales". They were later printed in one volume as Twinkle and Chubbins, which is currently available under Baum's name from IWOC.

- Policeman Bluejay (Laura Bancroft, 1907) — later reissued as Babes in Birdland in 1911, and again in 1917 with a new introduction by Baum and crediting Baum as author for the first time. Also published under Baum's name by Scholars' Facsimiles and Reprints, and in Oz-Story No. 2 (1996). Both books by "Laura Bancroft" are also available in a collected edition called The Twinkle Tales, published in 2005 by Bison Books.

- Tamawaca Folks (John Estes Cook, 1907). Available from Lulu.com.

- Annabel (Suzanne Metcalf [misprinted as Susanne Metcalf on the cover of the second edition], 1906) — reprinted under Baum's name in Oz-Story 6, and later as a separate volume from Hungry Tiger Press in 2006.

- The Fate of a Crown (Schuyler Stanton, 1905). Now available from Lulu.com.

- Daughters of Destiny (Schuyler Stanton, 1906) — reprinted under Baum's name in Oz-Story 4 (1998), and on its own by Hungry Tiger Press under Baum's name in 2005.

- Aunt Jane's Nieces (Edith Van Dyne, 1906), reprinted in 2003 by the International Wizard of Oz Club.

- Aunt Jane's Nieces Abroad (Edith Van Dyne, 1906).

- Aunt Jane's Nieces at Millville (Edith Van Dyne, 1908).

- Aunt Jane's Nieces at Work (Edith Van Dyne 1909).

- Aunt Jane's Nieces in Society (Edith Van Dyne, 1910).

- Aunt Jane's Nieces and Uncle John (Edith Van Dyne, 1911).

- The Flying Girl (Edith Van Dyne, 1911) — reprinted under Baum's name in Oz-Story No. 3 in 1997, and now available as a separate volume, published under Baum's name, from Hungry Tiger Press.

- Aunt Jane's Nieces on Vacation (Edith Van Dyne, 1912).

- The Flying Girl and Her Chum (Edith Van Dyne, 1912) — reprinted under Baum's name in 1997 by Hungry Tiger Press.

- Aunt Jane's Nieces on the Ranch (Edith Van Dyne, 1913).

- Aunt Jane's Nieces Out West (Edith Van Dyne, 1914).

- Aunt Jane's Nieces in the Red Cross (Edith Van Dyne, 1915) — a new ending was added to this story for its 1918 reprint.

- Mary Louise (Edith Van Dyne, 1916).

- Mary Louise in the Country (Edith Van Dyne, 1916).

- Mary Louise Solves a Mystery (Edith Van Dyne, 1917).

- Mary Louise and the Liberty Girls (Edith Van Dyne, 1918).

- Mary Louise Adopts a Soldier (Edith Van Dyne, 1919)

- As Edith Van Dyne, Emma Speed Sampson wrote three more Mary Louise books after Baum's death — Mary Louise at Dorfield (1920), Mary Louise Stands the Test (1921), Mary Louise and Josie O'Gorman (1922) — and also wrote two titles for a brief Josie O'Gorman series, Josie O'Gorman (1923) and Josie O'Gorman and the Meddlesome Major (1924).

- (The Aunt Jane's Nieces books were almost as popular as the Oz books at the time — so popular that other publishers wanted to issue books by "Edith Van Dyne." One publisher was so insistent on meeting Miss Van Dyne that a female Reilly and Britton employee was sent to meet with him, playing the role of Edith Van Dyne. She very graciously turned him down. Frank and Maud Baum also attended the meeting, under assumed names.)

In addition to all these books, Baum wrote numerous short stories and poems that appeared in newspapers and magazines, song lyrics, plays (most unproduced), introductions, and essays on his work, as well as the screenplays produced by the Oz Film Manufacturing Company.

Has anyone ever written a biography of Baum?

Yes indeed. Baum's eldest son, Frank Joslyn Baum, collaborated with Russell P. MacFall on the first, To Please a Child, published by Reilly and Lee in 1961. It is long out-of-print, and can be difficult to find. Although an important book, it suffers from gaps and inaccuracies, and much of it has been surpassed by subsequent research. More recently, several biographies for young readers have been issued:

- L. Frank Baum: Royal Historian of Oz by Angelica Shirley Carpenter and Jean Shirley (1992).

- L. Frank Baum, Author of The Wonderful Wizard of Oz by Carol Greene (1995).

- Margaret, Frank, and Andy by Cynthia Rylant (1996). L. Frank Baum was one of three authors profiled in this book.

- L. Frank Baum by Jill C. Wheeler (1997).

- The Road to Oz: Twists, Turns, Bumps, and Triumphs in the Life of L. Frank Baum by Kathleen Krull (2008).

- L. Frank Baum (part of the "Who Wrote That?" series) by Dennis Abrams (2010).

Two more comprehensive adult biographies have also come out in recent years:

- L. Frank Baum: Creator of Oz by Katharine M. Rogers (2002).

- The Real Wizard of Oz: The Life and Times of L. Frank Baum by Rebecca Loncraine (2009).

Finding Oz: How L. Frank Baum Discovered the Great American Story by Evan I. Schwartz (2009) deals with Baum's life as it relates to his writing, but it's accuracy has been challenged by several Oz experts.

Chapters on Baum have been issued as part of biographical anthologies as well. A few small press books have focused on more detailed portions of Baum's life, suce as Baum's Road to Oz: The Dakota Years, edited by Nancy Tystad Koupal (2000), about Baum's time in the Dakota Territory and South Dakota; and a Baum family geneology, The Family of the Wizard: The Baum's of Syracuse (1999). Baum and Oz scholar Michael Patrick Hearn is working on a new biography of Baum, and his research was the basis for a 1990 American television movie about Baum, The Dreamer of Oz.